The legacy of John Stott through the Lausanne Movement

By Julia Cameron

John Stott was a colossus. As Jim Packer said on hearing news of his death in 2011, “He had no peer, and we should not look for a successor.” As decades pass, history will further unfold the extent of his influence on theological thinking, on preaching, on the tensions between the gospel and culture, on the development of a Christian mind, on evangelical commitment to social justice and, supremely, on world evangelization.

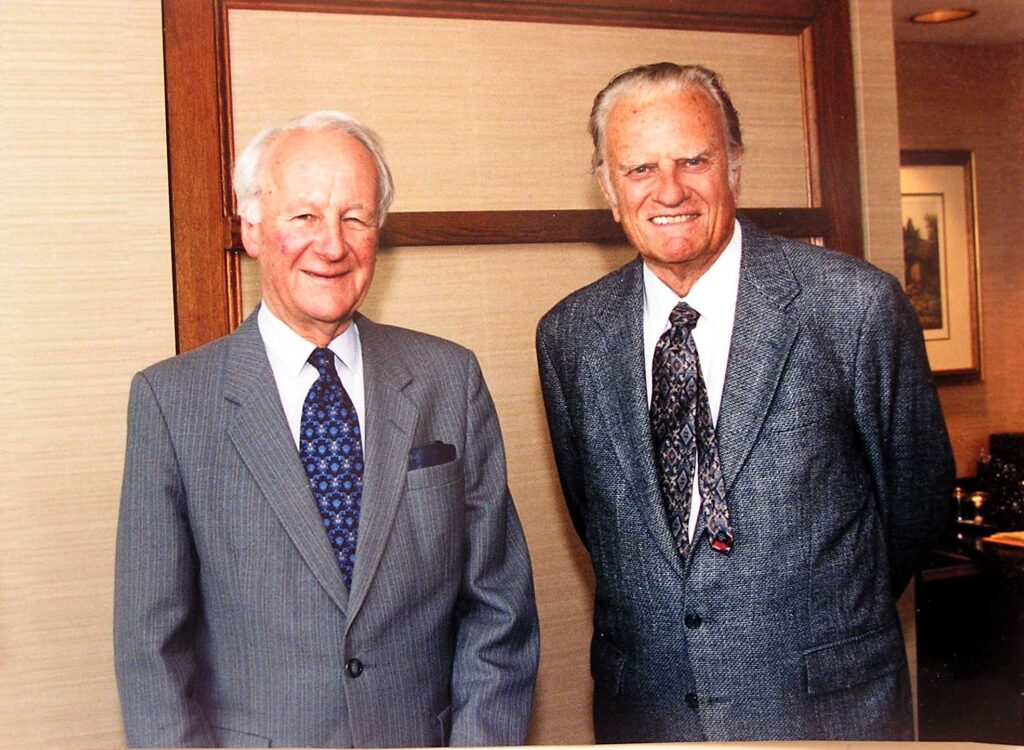

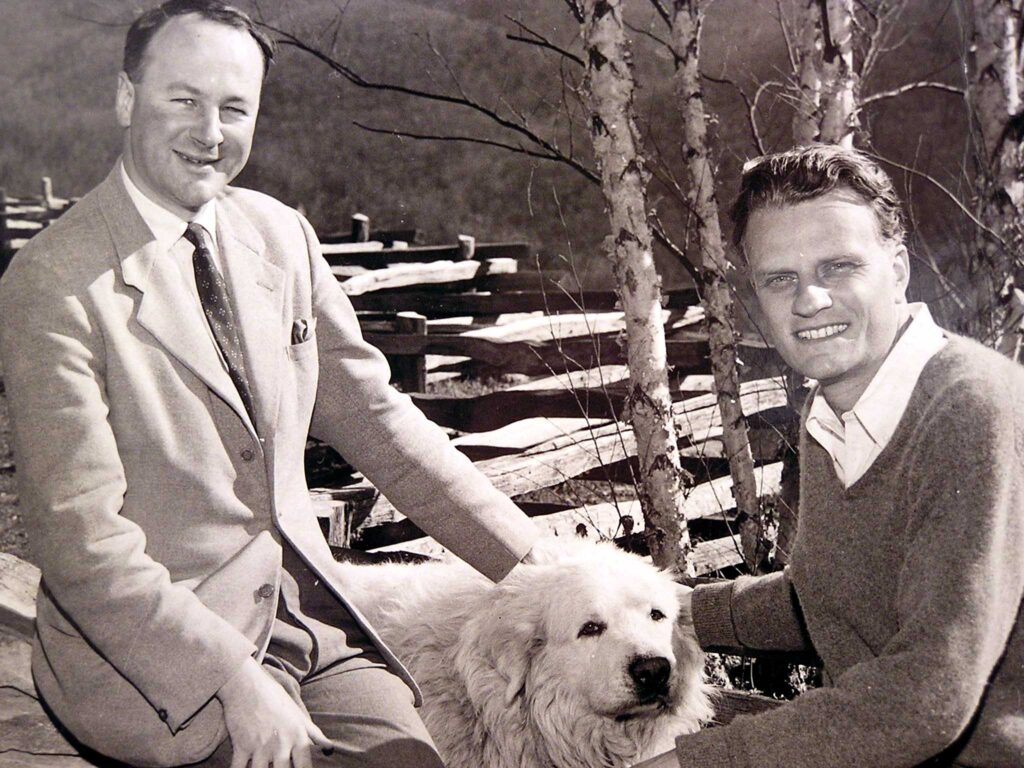

It was the unique partnership between Billy Graham and Stott which would launch the Lausanne Movement, a movement committed to “the whole gospel for the whole world” (later expanded to include both “the geographical world, and the world of ideas”). It brings together Christians leaders from around the world to further global evangelism.

Stott’s Two Priorities of Ministry

Stott said that the two priorities of his ministry were students and pastors, and this was clearly borne out. His three-pronged ministry (now drawn together as Langham Partnership) to help strengthen the church in the global south provided books for pastors and for students in seminaries, created scholarships for some of the most able thinkers to help them gain doctorates and provided training in preaching.

Stott’s relationship with the Lausanne Movement, particularly in the period of 1974-1996, could be described as reciprocal, even symbiotic. His multi-faceted ministry fitted the multi-faceted Lausanne aspirations, and Lausanne channels and networks would become a major means through which he brought influence to the church globally.

A Congress and a Covenant

His personal friendship with Billy Graham from the time of the Cambridge University mission in 1955 drew Stott into the early stages of planning for the 1974 International Congress on World Evangelization, held in Lausanne, Switzerland, and from which city the Movement would take its name. It was a friendship of spiritual genius from which, as we see, much would flow.

Stott was by this stage already regarded as a leader and figurehead, through participation in World Council of Churches events and in the 1966 Congress on World Evangelization in Berlin. The 1970s included seven or eight other international conferences. But from 1974, Lausanne was to have the lion’s share of his time.

John Stott’s reputation for clear theological thinking, his breadth of sympathy within the evangelical tradition and his gracious dealings with those of different persuasions made him an obvious choice to lead the process of crafting the Lausanne Covenant.

The Lausanne Covenant

The Lausanne Covenant, which reflected the voices of the 1974 congress, was adopted as a basis for hundreds of collaborative ventures over the rest of the century and came to be regarded as one of the most significant documents in modern church history. Social justice, too-long identified as a concern only for adherents to “a social gospel,” was now declared a biblical responsibility for evangelical Christians. This proved a watershed moment for the church.

Realizing the potential impact of the Covenant, John Stott worked on an exposition and commentary published in 1975. It would, he sensed, be critical for the Covenant to be read and studied by individuals and groups. His preface, modestly written, does not record the intense pressure of working through nights to ensure all comments received from the participants were given proper consideration. It was a mammoth operation to translate them in a timely manner, but it was vital for the voices of the whole evangelical church to be heard. The name “covenant” was carefully chosen. This was a covenant with God himself, and a covenant between all those who wanted to adopt it.

The Church’s ‘Mislaid Social Conscience’

In 1982, John Stott’s ground-breaking book Issues Facing Christians Today was published to coincide with the opening of the London Institute for Contemporary Christianity. This covered such matters as nuclear issues, pluralism, human rights, industrialization and sexuality. It became a handbook for pastors and thinking church members. It was, he said, his “contribution to the catching-up process” since the church was “recovering from its temporarily-mislaid social conscience.”

The Lausanne Covenant was continuing to create waves, reawakening a social conscience which had lain dormant in many quarters for perhaps two generations. The Lord Jesus had commissioned the apostles to teach new disciples “everything” he had commanded them. This had plainly not been done. In God’s grace, Stott and the Lausanne Movement would become a means of re-establishing significant aspects of Christian duty.

As a backdrop to his preparation of Issues, Stott continued to make Lausanne consultations a priority and was frequently the chair. He edited the papers from all the consultations up to Lausanne II and published them in 1996 under the title, Making Christ Known: Historic Mission Documents from the Lausanne Movement 1974-1989. As is clear from the contributors, Lausanne had the standing (helped, no doubt by Stott’s own presence) to draw the best evangelical thinkers globally. Some papers drew considerable traction.

The Lausanne Movement Legacy

In 2006, Doug Birdsall, then executive chairman of the Lausanne Movement, invited Stott to accept a lifetime title of honorary chairman, which he did, with a sense of pleasure. It had been a consistent pattern of his to accept honorary titles only if he could maintain a lively link with the endeavor, and he followed news of planning for the Third Lausanne Congress with eager and prayerful interest. Lindsay Brown, who was appointed as the Lausanne Movement’s international director in 2007, and Chris Wright, who followed in Stott’s own stead as chair of the Lausanne Theology Working Group, were both old friends.

Shortly before his 87th birthday, he surveyed his years in Lausanne and looked forward with anticipation to what Cape Town 2010 would bring. For as long as the Lausanne Movement is characterized by “the spirit of Lausanne” (a spirit of humility, friendship, prayer, study, partnership and hope), Stott sensed it would be critically placed. Christ gave gifts to his church to share. Lausanne provided the table around which these gifts could be shared.

An excerpt from “John Stott: Pastor, Leader and Friend”

(Dictum 2020). Edited and used with permission.

Julia Cameron, founder of Dictum Press, served as Lausanne’s Director of Communications, then of Publishing (2008-2019). Her books include an authorized biography of John Stott for children, to introduce him to the next generation; and an authorized biography of Frances Whitehead, Stott’s lifetime secretary. (Available from goodread.store.)